Did the Church Street Disaster undermine the Dublin Lock Out in 1913?

Christiaan Corlett • 7 October 2019

At about 8.45p.m., as dusk approached on the night of Tuesday 2nd September, 1913, two houses, Numbers 66 and 67 Church Street collapsed, killing seven people. For more information on the Church Street Disaster see my blog posted on the Dublin Tenement Experience Living the Lockout website, or see my book Darkest Dublin.

The question I want to ask here is, to what extent did the Church Street Disaster fuel the events of the 1913 Lockout in Dublin? I feel that during the recent debates and commemorations that have taken place to celebrate the centenary of the Lockout, the role of the Church Street Disaster and the Dublin housing crisis in undermining the trade union movement in their fight against the employers continues to be overlooked.

The link between the housing and labour crisis of that year is reflected in the fact that one of those killed in the Church Street Disaster, Eugene Salmon, was at the time locked-out of work in connection with the dispute at Jacob’s.(i) The Church Street Disaster on September 2nd took place only days after some of the worst disturbances of the labour strikes of 1913, which saw the deaths of two men during a baton charge by the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Many people questioned the use of force on that occasion:

“In every urban slum, in every rural slum, in every poisonous and insanitary house, the divine laws and the natural laws of life are broken…Why when the slums houses collapse and bury those who lived in them, why when report after report upon the housing of the poor has fallen on deaf ears, why when the divine law and the divine order have been broken and trampled on, why such indignation about the breaking of a police regulation”. ii

Contrasting the actions of the police on that occasion, one letter, signed A Dublin Citizen, to the editor of the Evening Telegraph, hailed the heroism of the firemen on the night the houses collapsed on Church Street:

“Truly, we men ought be grateful to them [the Dublin Fire Brigade] for having vindicated the proverbial manliness of Irishmen at a time when the appellation was jeopardised by the action of the uniformed hyena men who infest our streets beating the dying on the roadway and ill-treating the inoffensive citizens”. iii

In 1913 there was no such thing as the mass media that we have today. When we talk of the media in 1913 we mean the newspapers, and the newspapers were very influential in shaping the discussion of the day. In general the mainstream newspapers had little or no sympathy with the labour cause. Instead they readily embraced the slum crisis in Dublin as a more worthwhile one. While the city councillors had been calling for an inquiry into the police action at O’Connell Street on the weekend before the Church Street accident, The Irish Times felt:

“A tenant slum is a far worse menace to the lives of our citizens than the baton of the most infuriated policeman. The two houses in Church Street killed seven persons by their fall. For how much sickness and misery were they responsible”. iv

Another commentator wrote:

“Decently housed men would never have fallen such a complete prey to mob-oratory….The Church Street disaster has focussed public attention to a certain extent on the reality of this evil” v.

On 18th September a case came before the courts in which two brothers, William and Patrick O’Leary were accused of throwing stones at police. The two men and their families lived in a one-room tenement on the third floor at 2 Marlborough Place. William O’Leary lived in this room with his wife and six children. Also in the same room lived his brother Patrick, whose only child was dying of consumption. The next day The Irish Times featured an article entitled “O’Leary’s Rooms”:

“We ask our readers to consider that front room on the third floor of 2 Marlborough place from the aspects of economy, health, humanity, decency, their personal interests and the larger interests of the city. Is it economy to house the workers of Dublin in surroundings which make a clear mind, a strong arm and a cheerful heart – the essentials of good work – utterly unthinkable!….The poor child who is dying is not merely a grave danger to its six little cousins pent within the same four walls. It is a menace to the well cared and well fed children of every comfortable citizen of Dublin”. vi

This is a good example of the newspapers shifting the spotlight from the labour cause to the housing issue.

There were slightly different political reasons why Sinn Féin was more concerned with the housing conditions than the labour cause. Their newspaper argued:

“The vile and destructive methods of demagogues posing as labour leaders in Dublin will not divert the minds of honest and intelligent men from the fact that the poorest section of the population of Dublin has suffered and are suffering under an abominable grievance in regard to the houses in which they are forced to dwell.”

The paper concluded that Sinn Féin, contrasting the track record of labour representatives on the Corporation, was the only political party that “ever really attempted and really did something for the herded tenement dwellers of Dublin”. (vii) Commenting on the Dublin riots at the end of August, Arthur Griffith wrote:

“With luxury and extravagance flaunting themselves on all sides, there are unplumbed depths of misery and sordid grinding poverty in every fetid court and alley in Dublin and other Irish cities, want and disease in every crumbling tenement. Smouldering discontent and a sullen sense of enduring wrong, shared by a large section of the population, do not make for stability and progress”. viii

On October 4th 1913 James Larkin gave evidence to the Askwith Inquiry, and to the amusement of those in the room, he contrasted the slum conditions in Dublin with the conditions in Mountjoy Prison, where he had been imprisoned at the time of the Church Street Disaster. He directed the following scathing comments at the employers in the room:

“Let them take the statement made by their own apologist. Take Dr Cameron’s statement that there are 21,000 families—four and a half persons to a family living in single rooms. Who are responsible? The gentlemen opposite would have to accept the responsibility. Of course they must. They said they control the means of life; then the responsibility rests upon them. Twenty–one thousand people multiplied by five, over 100,000 people huddled together in the putrid slums of Dublin”. ix

Generally, however, the labour leaders did not make use of the slums as a political weapon. In the summer months of 1913 Larkin had been setting the foundations for the conflict with employers about workers pay and conditions, and by the end of August the positions had become irreversibly entrenched. Even before the Church Street Disaster, and the subsequent public outcry regarding housing conditions, Larkin had nailed his colours firmly to the mast, and he was not about to change tack. To rally to the universal call for improved housing might deflect attention from the battle at hand. This is clearly evident from Larkin’s own newspaper, The Irish Worker. In its edition of September 6th, four days after the Church Street Disaster, there was no reference at all to tragedy. However, later in the month, an article did appear in that paper, under the pen of William Patrick Partridge. In this article Partridge singled out the heroism of Eugene Salmon, and argued that his death was a direct result of poor pay and working conditions:

“From the debris of the fallen houses in Church street they bore the hero’s lifeless body – this time it was that of a boy of 17 years who worked in the factory of the sweater, Jacob, and who, through the miserable wages paid by this exploiter of the working classes, was compelled to risk his life in the tenements of the city … A few hours previous he had been dismissed because men refused to betray the hero leader, Larkin, and desert the faithful ranks of his gallant little Union fighting the fight of the oppressed and defenceless of the city. Young Eugene Salmon returned to the death-trap he called home, and as the mountain of blinding debris piled around him the young hero saved his baby sister and five others of the family…

Young Salmon, the hero, was a member of the Union led by the hero, Larkin”. x

Partridge’s attempt to make parallels with young Salmon’s heroism on the night the houses at Church street collapsed, and the heroism of Larkin’s bigger struggle on behalf of the Union, made no significant reference to the housing crisis. Indeed, Larkin and the Union arguably made a gross miscalculation by ignoring of the potential of the housing issue to strengthen their hand. With the middle classes united in their condemnation of the slums, Larkin had an opportunity to graphically show how this was a direct result of poor working conditions. However, if Larkin felt that the slum issue might undermine his own cause, by not taking ownership of the housing debate, he effectively gave employers such as William Martin Murphy a free reign to use the Church Street Disaster and the housing crisis to portray an empathy with the working classes.

This is evident from the way in which the Church Street Disaster and the slums became embroiled within a debate raging amongst the Dublin intelligentsia. In 1908 Hugh Lane had established a Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in temporary premises on Harcourt Street. For some time Dublin Corporation had attempted to secure funds in order to commission a permanent home for the gallery – a building designed by Lutyens that would span the River Liffey itself. Some commentators felt that the monies needed for the gallery would be better spent on improving the housing conditions of Dublin’s citizens. Leading the charge was none other than William Martin Murphy, owner of The Irish Independent, and the driving force of the employers’ lockout.

The day before the Church Street Disaster The Irish Times published a letter from Murphy, beginning with the sentence “like the poor the Art Gallery we have always with us”, in which he stated that his offer to provide the costs for housing the gallery at an alternative site had been snubbed by the Lord Mayor. This then seems to have been the true root of his antagonism towards the proposed gallery. It was only after the Church Street Disaster that Murphy justified his position on the gallery in terms of money being wasted at the expense of the housing conditions of the poor.

Within a week of the Church Street Disaster Murphy wrote a letter to the editor of The Irish Times in which he castigated the Corporation for squandering money on the proposed gallery:

“It is revolting to think that the week of the Church Street holocaust, for which the Corporation, as the authority … is responsible, should be the time selected for calling another special meeting of that body to force on against the wishes of the vast majority of the citizens the discredited project of spending money in building a picture palace over the River Liffey…The bad housing condition in the city, which is the cause of the Church Street disaster, is the question of questions for Dublin”. xii

The following day Murphy used his own paper, The Irish Independent, to make another attack on the Corporation:

“Yesterday the Corporation provided another comedy for the citizens in connection with the Art Gallery site. This performance would be extremely laughable but for the deplorable calamity in Church Street”. xiii

A few days later the paper returned to the issue and, noting that the proposed Art Gallery was not defined as a Dangerous Building, argued that:

“for the £22, 000 proposed to be squandered on an impossible Art Gallery the Corporation might provide 210 families with 110 decent, comfortable houses”. xiv

On the 16th September The Irish Independent reproduced five photographs of slums, entitled “Dublin’s Crying Evil”. The extended caption claimed:

“Our photographs give an idea of the appalling conditions under which the Dublin poor are obliged to live. The Church Street Tragedy, with its holocaust of humble victims, should have taught our Corporators a lesson, but heedless of the warning, they spend their precious time discussing egregious Art Galleries and Continental Art Schools. Meanwhile, there is danger of the Church Street Tragedy been repeated at any moment in many parts of the city”.

The following day the paper published three photographs of Dublin slums, beneath the heading “And they still think of Art Galleries!”.

The editorial of Sinn Féin made a sarcastic retort:

“The poor are indebted to the pictures for the discovery of their deplorable condition. The unemployed – the homeless – the occupants of rickety tenements, were without hope in the world until a home for the pictures was contemplated. The poor but for this chance may have died in ignorance of the wealth of love for them which lay hidden and unknown in the hearts of their fellow citizens”. xv

Patrick Pearse called on the rich men “who knew all about everything, from art galleries to the domestic economy of the tenement room”, and who claimed £1 a week was enough to “sustain a Dublin family in honest hunger” should give up their wealth and see for themselves the reality of living in slums:

“I am quite certain they will enjoy their poverty and hunger…When their children cry for more food they will smile; when their landlord calls for rent they will embrace him; when their house falls upon them they will thank God; when policemen smash their skulls they will kiss the chastening baton…in the alternative they may see there is something to be said for the hungry man’s hazy idea that there is something wrong somewhere”. xvi

In conclusion, I would argue that the Church Street Disaster, and the consequential interest taken by the newspapers in the housing crisis in Dublin, had a profound impact on the trade unions attempts to challenge the employers. By not using the housing crisis as an additional weapon in their arsenal, they effectively handed over the issue lock-stock and barrel to the media, and in particular William Martin Murphy was only too happy to take on the role as defender of the disenfranchised tenement dwellers of Dublin, if only to convince the middle classes that housing, and not workers rights, was the core issue at stake. With the middle classes convinced that a solution to the housing crisis was of primary importance, the employers had a freehand to play hard ball with the trade unions. Arguably, if Larkin and the trade unions had used the Dublin slum issue highlighted by the Church Street Disaster, it could only have strengthened their hand against the employers, and perhaps the outcome of the Lock Out would have been very different.

Despite its suggestions of modern forms of music and related art forms, rock art is the name applied by archaeologists to a particular form of prehistoric art found in northern and Atlantic Europe. Indeed, rock art is found in many parts of the world; suffice to say here that they are not contemporary or even directly comparable in terms of function. In Ireland rock art is usually found on a boulder or stone outcrop in the open landscape, while some smaller examples may have been intended as portable objects. In this way rock art is very different to the art found on the architectural stones of some Neolithic passage tombs in Ireland, such as those in the Boyne Valley or on the hilltops of Loughcrew, Co. Meath, where the art is integral to the monuments. In Ireland what makes rock art significant is that it is thought to represent the earliest known art form in the country. It most likely dates to the early Neolithic and is probably earlier than the art found in Neolithic passage tombs. Rock art is found across much of Ireland, with dense concentrations along some western coastal areas such as the Dingle and Iveragh peninsulas of Kerry, the Inishowen peninsula of Donegal, as well as parts of Cork. Rock art is also found in smaller but growing numbers in mid-Ulster, notably Cavan, Fermanagh and Monaghan, as well as in north Leinster, notably Meath and Louth. The Carlow rock forms part of the south Leinster distribution, that includes Kildare and Wicklow. The impressive concentrations of rock art in counties Cork, Kerry and Donegal have largely overshadowed those elsewhere in the country. One area that has received little attention is Carlow, yet in recent years it has become clear that the county is much richer in rock art than previously thought. In Carlow, rock art is most densely concentrated in the southern part of the county, around Borris and Myshall, extending from the River Barrow to the foothills of Mount Leinster and the Blackstairs. In recent years several examples have been found further north, in an area between Bagenalstown and Myshall. The only example to date known from Kilkenny was found on the lower slopes of Brandon Hill overlooking St Mullins, and forms part of the general distribution of the south Carlow rock art. This stone, and the decorated stone at Fenniscourt, Co. Carlow are the only rock art sites presently known west of the River Barrow.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, most, if not all farms, kept poultry such as chickens, ducks and sometimes turkeys. Sitting hens were most commonly kept in the kitchen until the eggs had hatched and the chicks were a few weeks old. Adult and young poultry spent their entire daytime life outdoors, free to range throughout the farmyard and haggard. At night they had to be protected from predators such as foxes and pine martins. The structures to keep poultry safe at night were often timber structures that might be quite temporary structures that might be replaced every few years and leave little or no trace today. However, in some areas of Wicklow, most notably the south and west of the county, more permanent, stone structures commonly called duck houses were used. These typically comprise a small dry-stone chamber built into a bank or wall, and always positioned in the farmyard within easy view of the kitchen door of the farmhouse. The purpose of these was simply to provide a safe place for poultry at night and protect them from hungry foxes. In March 1959, Liam Price was shown four duck houses at Fogarty’s farm at Balleeshal near Aughrim. He described them as ‘Four recesses: each has a square entrance a foot or so wide and about the same height: inside they enlarge into a rounded space about 3ft across, and are covered with a sort of some of stones’. Price was told that they were duck houses, and that each could accommodate four or five ducks, and ‘you put a stone over the entrance, and the ducks were then perfectly safe from foxes’ (Corlett & Weaver 2002, 642). The farmhouse was then in ruins and today no longer survives. Fortunately, I have been able to record others in the county, such as an example at Slievenamough, near Rathdangan (Fig. 1). The straight-sided chamber is 55cm wide, 85cm deep and originally about 50cm high. The entrance to the duck house at Lockstown Upper (Fig. 2) is 50cm wide and 50cm high. As well as the entrance lintel, the interior of the chamber (which measures just 70cm wide and 1.2m deep) is spanned by two large flat slabs. Though quite simple structures, I find them particularly intriguing, not least because the form of construction is quite archaic. However, despite the fact that they resemble similar structures found at some early medieval sites, such as stone cashels, during the 19th and early 20th centuries in Wicklow and neighbouring Carlow, it appears that these chambers were specifically reserved for poultry.

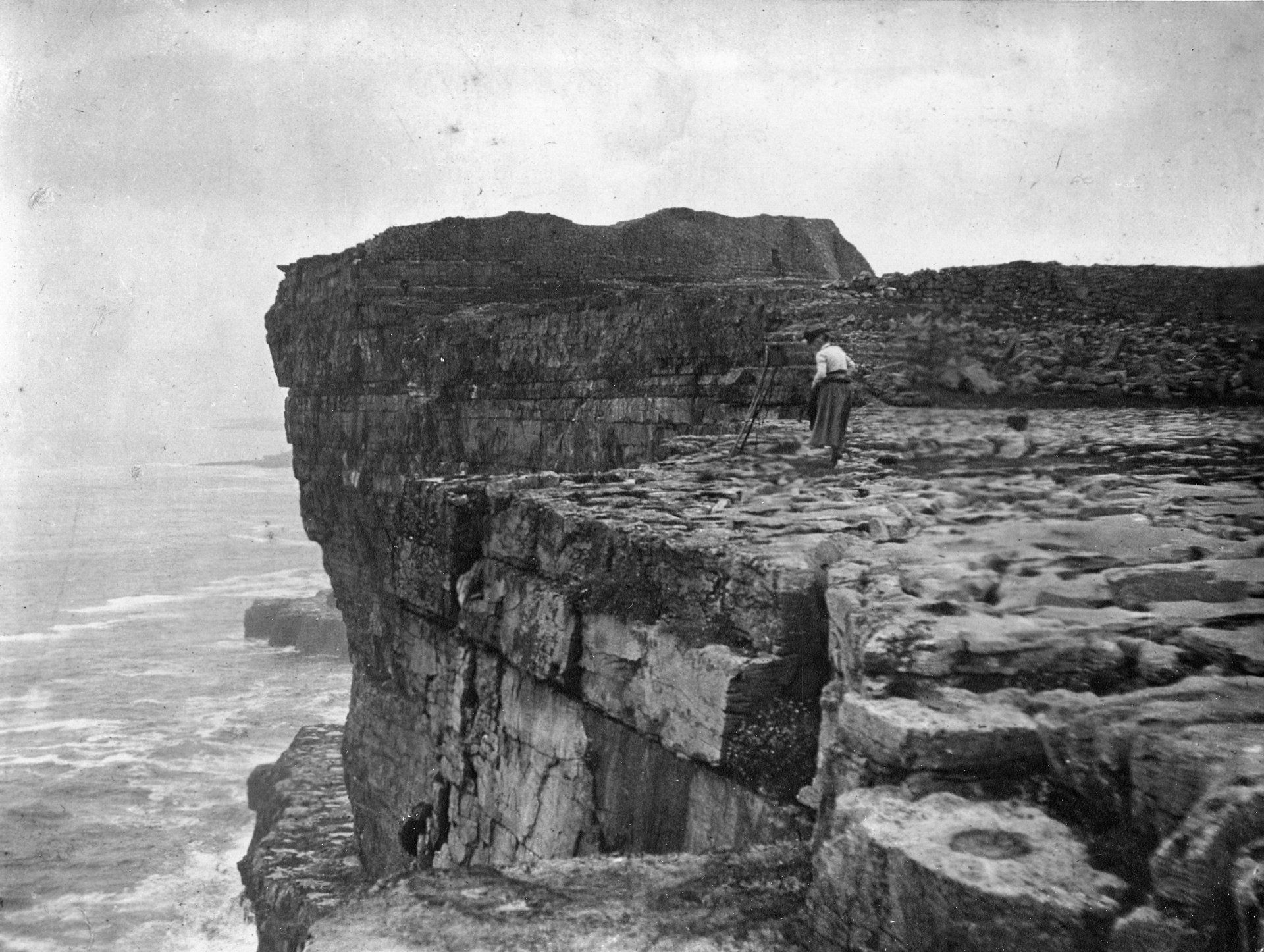

One of the largest collections of early photographs taken by a female photographer in Ireland were taken by Jane W. Shackleton (née Edmundson, 1843-1909). Mrs Shackleton was from a well-established Quaker family that could claim descent from William Edmundson, who held the first Quaker meeting in Ireland in Lurgan in 1654. During the later 19th century and early 20th century, an interest in photography was a feature of many Quaker families. The most famous of these was the Belfast photographer, William A. Green (1870-1958), and his photographic interests are broadly similar to Jane W. Shackleton. A lesser known, but highly skilled Quaker photographer was Robert L. Chapman (1891-1965). Jane Wigham Shackleton was the daughter of Joshua and Mary Edmundson. Joshua Edmundson (1805-48) had established a firm in the 1830s at 35 and 36 Capel Street, Dublin, called Joshua Edmundson & Co. that was described as ‘house furnishers, iron mongers, cabinet makers, upholsterers, plumbers, gas fitters, brass & iron founders, gas, lighthouse and sanitary engineers, electricians’. In March 1866 Jane married Joseph Fisher Shackleton, of the famous Shackleton family whose Irish roots were established in Ballitore, Co. Kildare in the early 18th century. Joseph Shackleton’s father George decided to expand the Ballitore milling business by establishing an office at 35 St. James’ Street in Dublin and acquiring three mills in the Lucan area of County Dublin. The Dublin mills were at Grange and Lyons (on the 12th and 13th locks of the Grand Canal) and Anna Liffey on the River Liffey. Joseph Shackleton managed the three mills, and he and Jane established their home beside the mill at Anna Liffey. The Anna Liffey Mill produced the famous Lily of the Valley flour, as well as semolina, ground rice and wheat, and worked until 1998. The origins of Jane W. Shackleton’s interest in photography are shrouded in mystery. It appears that she first began taking photographs in the mid 1880s, and from the outset processed her own prints from the negatives at Anna Liffey. From about 1889 Jane W. Shackleton began producing lantern slides from her photographs. At this time Jane W. Shackleton occasionally found herself giving lectures to various groups, and illustrated these with her own lantern slides. As well as the lantern slides, several volumes of her lecture notes also survive. Generally these give little insight into her developing interest in photography, but it does appear that she did not see herself as an accomplished photographer. While it may be true that she did not have great technical skills, Mrs Shackleton’s photographs display a very intelligent choice of subject matter and composition. It appears that Jane W. Shackleton first began taking photographs of her six children, extended family members and friends in the mid 1880s. Soon Jane W. Shackleton began to include subjects of local interest around Lucan, and the family connections with Ballitore and Mountmellick are also reflected around this time. As the children grew older, family excursions became more numerous and more adventurous. In 1888 Jane W. Shackleton and her husband spent three weeks in Norway, where they took an interest in an 18ft boat built on the Hardanger Fjord. Sometime later this boat arrived at Anna Liffey, and in 1889 the family took this boat by rail to Carrick-on-Shannon from where they spent ten days travelling down the River Shannon to Killaloe. Over the coming years the family made regular trips along the Shannon, as well as the Grand Canal. In 1892 Jane W. Shacketon was elected a member of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, and she regularly participated in the Society’s trips around the country. This presented Jane W. Shackleton with even greater opportunities to visit many more places around the country. The west of Ireland, and in particular the Aran Islands, was a favourite subject of many photographers at this time. Many of Jane W. Shackleton’s contemporaries tended to focus on either people or places, in particular the rich archaeological remains of that part of the country. However, more than most photographers of the time, Jane W. Shackleton tended to encourage local people to be part of her photographs. Some photographers, such as Robert Welch, frequently included young children who were carefully placed and often in side profile. Jane W. Shackleton included much larger groups of people of all ages. While these people are always placed in the photograph, Jane W. Shackleton does not appear to have contrived their positioning, resulting in more natural looking portraits than was usually the case at this time. Jane W. Shackleton first visited the largest of these islands, Inis Mór during a five day trip in August and September 1891, and she returned to the island in July 1892. Apart from these personal trips to Aran, she also visited the islands on shorter occasions as part of the archaeological excursions organised by the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in July 1895, June 1897, July 1901 and June 1904. She last visited Inis Mór in April 1906. During her visits to Inis Mór, Mrs Shackleton regularly photographed the children attending the various schools on the island, such as at Onaght and Killeany. In particular she seems to have developed a relationship with David O’Callaghan, the teacher at Oatquarter since 1885. He became actively involved in trying to improve the lives of the islanders, and unlike many of his colleagues elsewhere in the country, he passionately believed in the importance of the Irish language and teaching in the Irish language also. This is reflected in what appears to have been Jane W. Shackleton’s first encounter with the teacher when she arrived in a cruise ship Caloric that anchored off Kilmurvey in July 5th 1895. Jane W. Shackleton was one of a large party of members of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland that had visited several islands along the west coast before arriving off the Aran shoreline. According to her subsequent lecture notes: “Soon canoes [curragh’s] came off from the shore. From one of them a respectably dressed man came on board; he was the school master from Oatquarter, one of the villages. He had brought his children to show them the steamer. He inquired gravely “Is the Society going to make investigation of the oldest monument of all” – “What may that be?” he was asked. The Irish language was the reply. He went on to suggest that perhaps some of the learned gentlemen would give an address to the islanders in their native tongue! He sang some songs in Irish, as also did some of the island men & they danced some jigs for the amusement of the company”. She noted that the schools were given a holiday in honour of the Society’s visit - primarily because if they had not been given a holiday they would have taken it. In April 1906 she visited the school at Oatquarter and arranged with David O’Callaghan to photograph the school children. In a letter to her family she describes the girls singing some Irish songs for them: “Then came the photographing – a troublesome job as it was very windy. First the boys - & then the girls. They all look hearty & healthy – very clean and well dressed, mostly in white and red flannel”. Mrs Shackleton took an active interest in many of the people that she met. During a visit in July 1895 she met and photographed Bridget Mullins; “The people were so glad to be photographed & were very obliging in bringing out a spinning wheel as I had expressed a wish to see one. The spinner was so grateful for the photographs I sent her that she sent me shortly after a pair of stockings that she had knit for me from wool of her own spinning”. At one point in her lecture notes Jane W. Shackleton commented that: “There is no difficulty in finding guides – even if you do not want them – they will keep by you for half a day for the pleasure of your society”. In particular she was fond of a young boy named Michael Dillane who seems to have been a frequent companion and she felt that in time he would make an excellent guide for visitors to the island. These were not the only islands visited and photographed by Jane W. Shackleton. In 1894 she personally visited Iniskea, Co. Mayo and Inishmurray, Co. Sligo. In July 1895 she revisited Inishmurray and also stopped off at Tory Island, Co. Donegal and Clare Island, Co. Mayo, as part of a cruise around the northern and western coast of Ireland organised by the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. The Society organised a number of similar cruises at this time in the hope of bringing public attention to some of Ireland’s most extraordinary and inaccessible archaeological monuments. When the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland visited Inishmurray in July 1895 the island’s King, Waters, was on the mainland, so instead they were received by Heraughty. Jane W. Shackleton was already acquainted with Heraughty, having visited Inishmurray the previous year. She later wrote: “Heraghty received us on landing & was most kind in showing us all he could in the time. He met me as I went ashore from the Caloric’s boat with a hearty welcome - inquiring for the others who had been with me before ... he ought to be Righ or King as his father before him - but his mother married again & his step brother Waters now seems to be the leading man on the island”. In fact, the island was repopulated in the early 1800s, and it was decided to instate the title of King of Inishmurray in keeping with the long standing traditions of other western islands such as Tory and Iniskea. However, the title on Inishmurray was largely nominal and came with little of the authority that the so-called kings of other islands enjoyed. Jane W. Shackleton wrote that Heraughty took the group to see the holy well known as: “Tober-na-coragh, meaning the Well of assistance. The legend attaching to it is that when there are storms of long duration preventing communication with the mainland if the waters of this well are drained off into the Atlantic and certain prayers offered, a calm will ensue. Surely this may be considered a relic of paganism, and yet our friend Heraghty spoke of it in all seriousness.” Heraghty’s daughter seems to have been keen to leave the island and visit the Shackleton’s home at Anna Liffey; “She was very anxious to see a little of the world outside her island home and entreated me to ask her Dada if he would let her go by train to pay a visit to us, but I put it off to some future occasion.” During the early 1900s Jane W. Shackleton was still visiting many parts of the country and actively taking photographs. However, in 1906 her mother, Mary Edmundson died, and her husband Joseph suffered from a stroke. This seems to have brought a sudden end to her photography. Joseph died in April 1908, and on 5th April 1909 Jane W. Shackleton herself died. The Shackleton family continued to operate the mill at Anna Liffey for many years to come, but for many decades the photographs were forgotten. Today the collection consists of over 1000 lantern slides and several thousand prints contained in 44 albums. Unfortunately, the original negatives of these photographs are almost entirely lost – only 58 negatives survive, all of which are glass plates. Despite this, the collection of photographs is a substantial one by any standards and because Jane W. Shackleton was so astute at recognising the importance of a subject, a very large proportion of the photographs are of tremendous historical value.

Glendalough, in the heart of the Wicklow Mountains, translates from Irish as ‘the glen of the two lakes’. These are known today as the Upper Lake and the Lower Lake. Some readers may be familiar with the stories of a monster at Glendalough. The earliest account we have of this monster story comes from one of the Irish Lives of St Kevin , who founded the famous monastery there. According to this story none other than Fionn MacCuamhaill prophesised that Coemgen (i.e. Kevin) would overcome a monster in the lower lake of Glendalough; “There was a horrible and strange monster in the lake, which wrought frequent destruction of dogs and men among the fiana of Erin. Coemgen recited his palms, and entreated the Lord, and He drove the monster from him into the other lake. That is to say, the lesser lake, in which the monster (originally) was, is the place where now help of every trouble is wrought both for men and cattle; and they all leave their sickness there, and the sicknesses and diseases go into the other lake to the monster”. There are a number of key elements to this story. Firstly, St Kevin, with the help of God, drives an evil monster from the lower lake to the upper lake. Secondly, it is clear that the lower lake was associated with cures, not just for human ailments, but for cattle also. Finally, the implication of this is that the lake had curative properties in pre-Christian times, before Kevin banishes the monster. When first reading this passage closely, I was immediately struck by how similar some of these elements are to a number of known to have been Lughnasa sites. For example, writing a description of Westmeath in 1682 Sir Henry Piers commented that it was traditional on the first Sunday in August (i.e. Lughnasa) to ‘drive their cattle into some pool or river, and therin swim them’. In 1808 these traditions were still strong in Westmeath, and it was recorded that the locals were still swimming their horses on ‘Garlick Sunday’. At Lough Owel, also in Westmeath, the Lughnasa traditions consisted of a horse race in the lake, and a report of one of these in 1818 tells how a young man was pulled off his horse and killed by a monster. In 1838 Thomas O’Conor of the Ordnance Survey recorded the traditions associated with Loughkeeran near Bohola, Co. Mayo, on the last Sunday of July; “The people, it is said, swim their horses in the lake on that day, to defend them against incidental evils during the year, and throw spancels and halters into it, which they leave there on the occasion. They are also accustomed to throw butter into it, with the intention that their cows may be sufficiently productive of milk and butter during the year”. Similar stories have been documented concerning St Marcan’s Lough in Clew Bay, also in Mayo. Clearly, the association of swimming horses and cattle at Lughnasa was a very ancient tradition that was originally seen as having preventative powers rather than simply curative ones. That St Kevin overcomes a monster at Glendalough is also reminiscent of the stories of St Patrick overcoming a monster at Croagh Patrick, Co. Mayo, which he banished to Lough Nacorra on the southern slopes of the mountain. Croagh Patrick is the focus of the largest surviving pilgrimage in the country, which takes place on the last Sunday of July. Arguably, Croagh Patrick is the finest surviving example of a Lughnasa site anywhere in the world. In 1904 Lord Walter Fitzgerald documented the local placenames in Glendalough, and recorded that the lower lake was then known as ‘Lough-na-Peestha, .i.e. the lake of the serpent. Even as recently as a hundred years ago the story of St Kevin overcoming a monster or serpent in the lower lake was still strong. Interestingly, there is also the added dimension in these more recent traditions that St Kevin overcame the monster with the help of his wolfhound ‘Loopah’. And what of St Kevin himself? While it is easy to read too much into the story that his greatness was supposed to have been prophesised by Fionn MacCuamhaill, it may be much more significant that all sources agree that Kevin’s father was Caomhlugh, caomh meaning ‘fair’, and Lugh almost certainly derived from the name of the ancient Irish god of Lughnasa. While there is disagreement about the dating of the various Lives of St Kevin, all agree that they were written several hundred years after his death. It is therefore dangerous to transfer too much from these Lives back to the time of St Kevin, let alone before his time. And while the evidence for a Lughnasa connection with Glendalough is tenuous, it is also very tempting and finds significant parallels with known Lughnasa sites elsewhere in the country. Firstly, there is the story of St Kevin overcoming a wild monster in the lake, which finds parallels with other sites, such as St Patrick at Croagh Patrick, but also at Lough Owel, Co. Westmeath, where part of the Lughnasa tradition of racing horses in the lake may have been all the more exciting because of the presence of a monster in the lake. Indeed, such traditions of lake monsters may ultimately be a corruption of an anti-Lugh deity in pre-Christian times. There is also the tradition of men and cattle coming to the lake at Glendalough for cures, which is typically associated with Lughnasa sites elsewhere in the country. Finally, there are the possible connections between St Kevin himself (i.e. through his father) and the ancient Irish god Lugh. If this is the case, then it raises a number of interesting issues. Firstly, it clearly indicates that Glendalough was not an isolated part of the Wicklow Mountains and the desirable location of a hermit (i.e. St Kevin) seeking isolation from the world. Instead, it tells us that the later importance of Glendalough, the ‘city of God’, owes its origins to a pre-Christian deity. It may also take us a step further, and force us to raise the question, was St Kevin himself a real person, or could he be a Christian personification of Lugh himself? By way of a postscript, and if only to thicken the plot – it might be worth noting that according to some sources, one of St Kevin’s successors was none other than St Moling. Máire MacNeill, in her book The Festival of Lughnasa, notes that the Fair of St Mullins in Carlow, rather than being associated with St Moling’s feast day on June 17th, was instead was associated with the feast of St James, i.e. 25th July (curiously, the infamous Fair of Glendalough was traditionally held on the last Sunday before St Kevin’s feast day, i.e. June 3rd, and was suppressed in the late 19th century). MacNeill provides a compelling argument that St Mullin’s was originally a Lughnasa site. Given the attempts in the Latin Life of St Moling to link the saint with St Kevin and Glendalough, it may be no coincidence that Fionn MacCuamhaill also prophesises the greatness of Moling. While this may not be significant in itself, what may be much more significant is Pádraig Ó Riain’s suggestion (in his book A Dictionary of Irish Saints ) that “the saint’s name may ultimately derive (through lu-n-g-/li-n-g-) from the divinity name Lugh”.

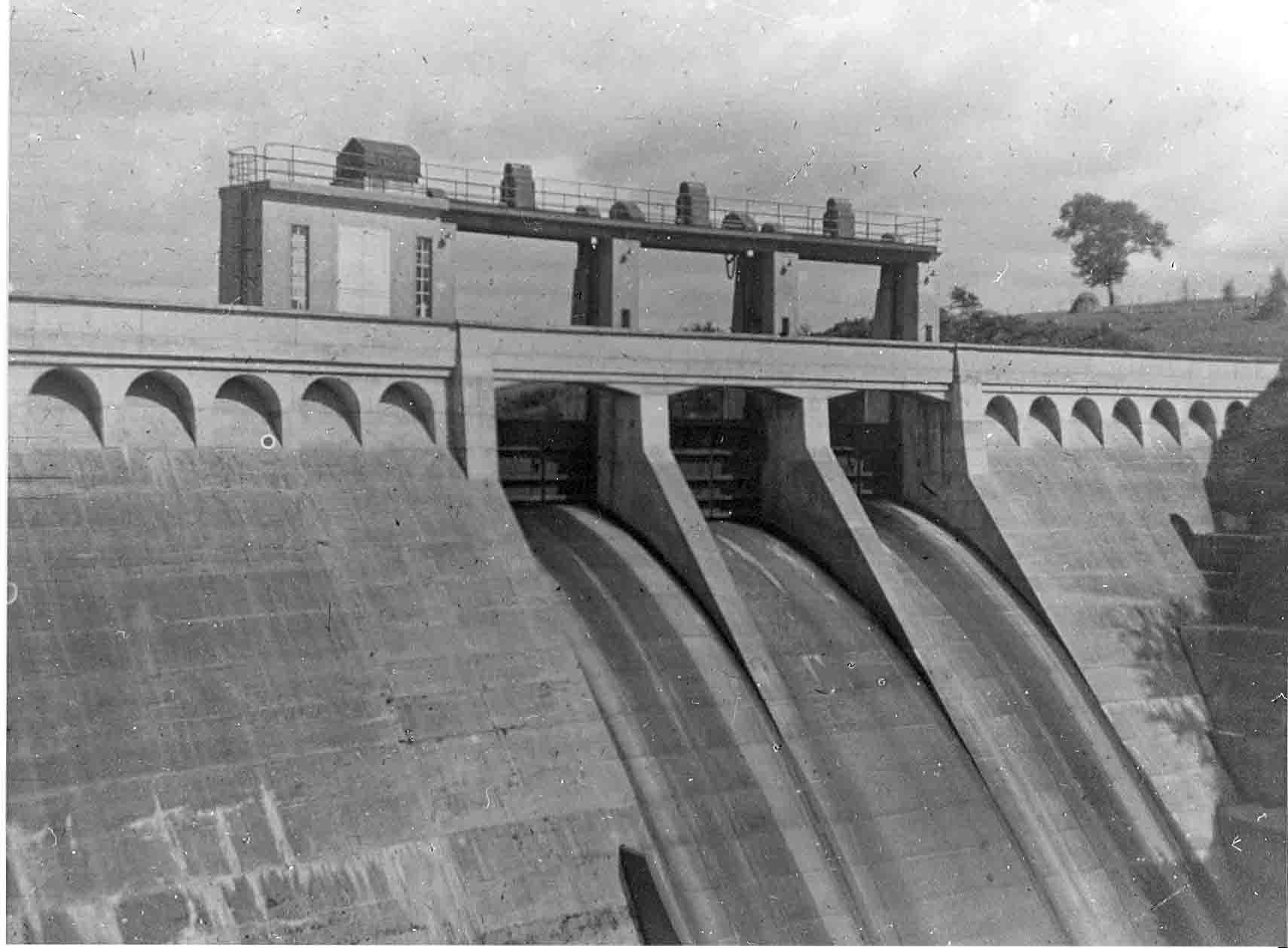

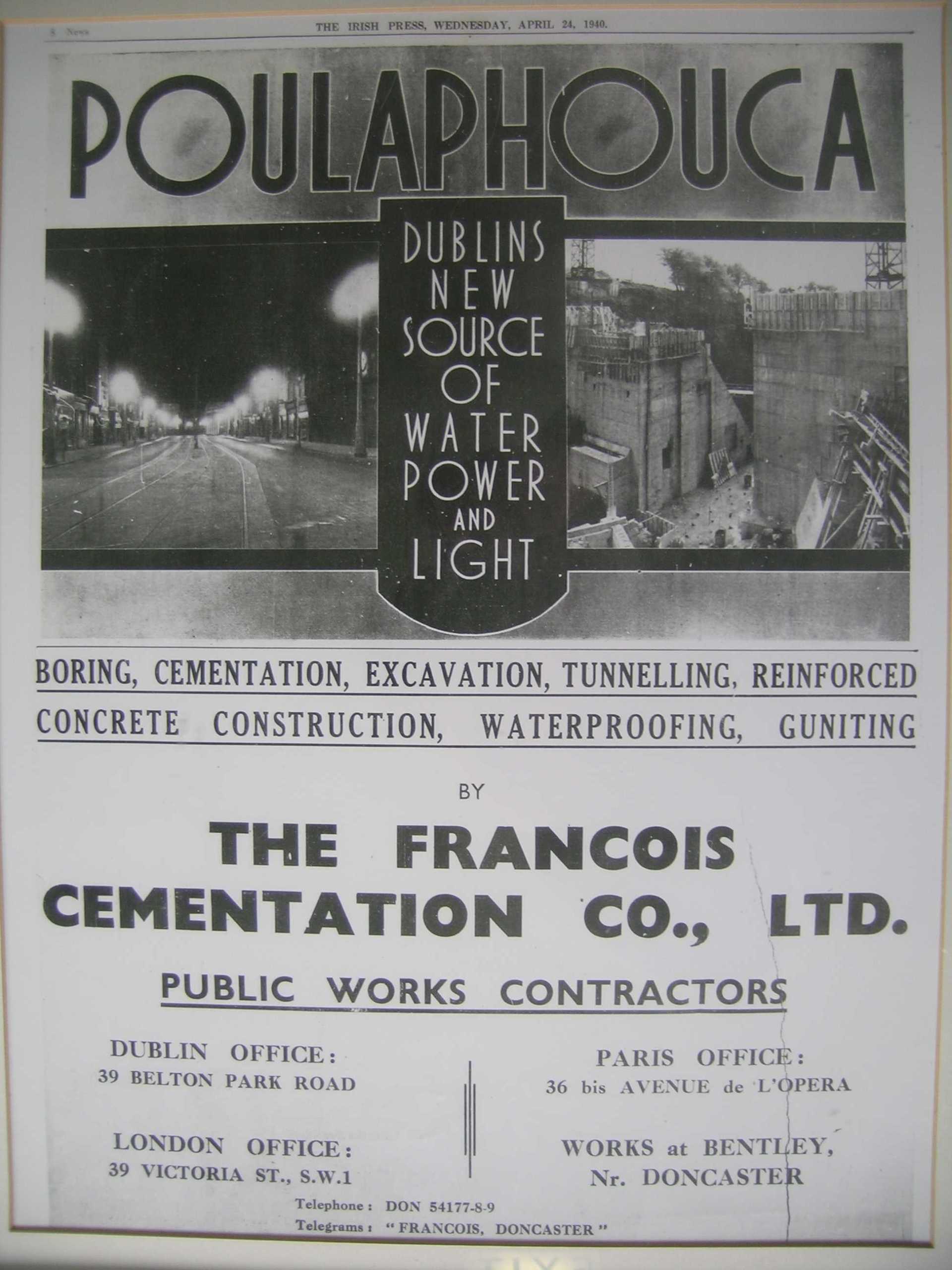

The target for the reservoir was the flooding of all the land in the area below the 188.4m (612ft) OD, with an aim of maintaining the low water level at no lower than 177 m (580ft) OD. Taking the 612ft OD as an average level of the reservoir, some 4960 acres (2007 hectares) would be flooded, creating a shoreline of over 30 miles. Additional to this, the E.S.B. also required a sufficient buffer area between the reservoir and the surrounding agricultural area, in case there was a need to raise the lake levels, and also to prevent contamination of the drinking water by farming. This buffer area was subsequently planted with forestry in order to prevent stock from gaining access to the reservoir, and to limit human access to the reservoir also. In effect over 5,500 acres (2225 hectares) would be affected by the proposed reservoir, including some 55 residential holdings and 12 labourers cottages, 50 farms and extensive bog land used for fuel by local families from a wide area. Some of the houses would not be flooded by the reservoir, however, in order to ensure the necessary quality of the water as a water supply, houses situated beside the proposed shoreline were to be purchased and demolished. The issues concerning compensation did not go away after the passing of the Liffey Reservoir Bill at the end of 1936. Indeed, it would become the focus of much resentment. Local political representations argued that the proposed measures could not compensate for the loss of independence that would impact certain farmers, and that there would be no compensation for disturbance caused to those forced to move. In particular, farmers whose holdings would be partially covered by the reservoir would also only receive compensation for the acquired land at market value, without any consideration of the impact the reduction of their farmland would have on their livelihoods. Speaking to one farmer who would be affected in this way, a journalist reported: “I talked to a man with thirty acres of land, twenty of which – and the best twenty – he expects to lose. He asked, reasonably; “What use is this house and ten acres of poorish mountain land? I cannot live on it, but I will not be compensated for the house, because it will not be flooded”. ( The Irish Independent , 6th October, 1937). For these farmers, who used much of the low lying ground as grazing for dairy farming, the loss of this land meant that they would be forced upland. This land was not suitable for dairy stock all year round, and meant that these farmers would be forced to change to another form of farming, such as sheep. There were also concerns about the effects of the reservoir on the holy well known as St. Bodin’s Well at Templebodin. According to tradition there were two fish in the well, which would escape once the area was flooded, thereby causing the well to loose its power (National Folklore Collection, Schools Manuscripts 913:131). There is a hint of sarcasm in a correspondent writing in the Irish Press: “Perhaps the believers in the old tradition will shake their heads in doubting; perhaps they will make the best of it and relate how it is that the Liffey hydro-electric scheme assumes its power from a blessed well”. ( The Irish Press, 28th March, 1938). This reflects a general change of attitude during this period, one which turned its back on the old ways, and saw not just the electric revolution, but also the scheme itself and the use of this technology to harness the power of electricity, as a means towards achieving a modern Ireland. One newspaper reporter wrote: “The seanachaidhe frowned. Who now would listen to the titanic prowess of the legendary heroes of old, when a number of ordinary, present-day mortals, without the aid of any magic wands or magic hokus-pokus, could transmute Anna Liffey into a form of tamed lightening that could do their bidding at will in a number of fantastic operations, such as lighting a whole city thirty miles away, driving trains, unloading ships, curling ladies locks, shaving men’s faces, taking pictures of people’s insides and throwing the voices of child prodigies, prophets and the like from one end of the world to another through the ethereal void in less than one flick of a Wicklow lamb’s tail – all sorts of things like that out of just ordinary water!” ( The Irish Press , 24th April, 1940). The protracted nature of the proposed scheme appears to have weakened any desire to vigorously oppose the scheme when it was finally proposed officially. This is evident from a newspaper report in 1936: “Ballinahown, while doomed, is prepared to accept what the future holds. “Eleven years ago”, I was told, “something like this was in the air, but they went off to the Shannon, and built there. Two years ago there was more talk about water works”. On that occasion, it would appear, notice was given to people who would be affected that their homes should not be repaired or added to in any costly nature. Since then no other information has been received, but, as the man here in the heart of affairs told me, “they mean business this time”.” ( The Irish Independent , 27th May, 1936. The informant was not named, but may have been one of the Quinn’s of Ballinahown). In an interview with John Quinn of Ballinahown in 1937, a journalist provides a valuable insight into the psychological effect the imminence of the scheme had on the communities: “He states that for the last ten years this depressing threat of dispossession has retarded development. He had noticed it depressing the young, progressive farmers, chilling their enthusiasm” ( The Irish Independent , 6th October, 1937). Local resentment was aired at several meetings held in the area during 1938 and 1939. Fr Francis O’Loughlin, Parish Priest of Valleymount was also critical of the scheme, and together with some local politicians, set up The Disturbed Owners Association to highlight deficiencies in the plan. The Chairman of the Association was Peter P. O’Reilly, who, in an interview with the Irish Press, came out in support of his fellow Ballyknockan stone cutters: “Above the valley 500 men work at the quarries. They are trade unionists, they care not for any other trade; they depend on the valley, some of them for produce of little gardens which they have patchworked into its marshes after years of toil, their work being from father to son; those who do not actually dwell in the valley, but in the foothills, depend on it for the grazing of their few cows, for turf from its bogs, their only source of fuel.” ( The Irish Press , 20th April, 1938). At the beginning of October 1938 a large protest meeting was held at Lacken. At this meeting many of the concerns were discussed, not for the first time. At the outset the chair of the meeting, Martin Murphy of Carrig, claimed that “no one was officially informed of his position, and the only notification they got at the start of the proceedings was from a map which was sent to the local Garda Station”. It would appear that even at this stage there was much confusion as to when people would be required to leave their houses and farms. There was also much resentment against the compensation offers made by the E.S.B., which were claimed by some to have been as much as £200 and £300 less that the estimates of the land valuers. At the end of the meeting a resolution was passed unanimously: “That we, the farmers of Blessington, Lacken and Valleymount, view with alarm the inadequate compensation offered by the Electricity Supply Board for our lands which are acquired for the Liffey Hydro Electric Scheme. The prices fixed in the original offers were considerably below the ordinary land values, and having regard to the consequential losses which will be entailed by all affected, and considering that we are forced from our lands against our will, we demand the fullest measure of consideration. In the event of arbitration, we demand that the arbitration court consists of one of the Electricity Supply Board, and an independent Chairman, who will be mutually agreed upon by both parties”. ( Leinster Leader , 8th October, 1938). Arbitration proceedings were held at Blessington in October 1938 for those who were dissatisfied with the standard compensation rate offered to them. A newspaper correspondent reported that at the opening of the proceedings John A. Costello, K.C., for the E.S.B (and future Taoiseach) refuted the perception that the arbitrator, J.J. McAuley, would be in some way biased in favour of the E.S.B. He stated that the appointment had been made by an independent committee, consisting of the Chief Justice, the President of the High Court and the President of the Institute of Civil Engineers. He further stated: “The E.S.B. had been charged by an Act with the gravest public responsibility and duty in connection with this scheme. A great hardship would undoubtedly be caused to individuals, but public purposes had a right to over-ride private grievance. The Board fully appreciated that numbers of these people would be dispossessed of their lands in which they had lived for generations, and that no amount of money would adequately compensate them for their sentimental loss or the sentimental value they attached to their holdings. The principle they had to follow, however, was laid down in the Liffey Act and there was nothing new in this principle on which the compensation must be assessed.” (Quotation of correspondent reporting in The Wicklow People , 15th October, 1938). Clearly there was no tolerance of sentimentality in the momentum for the improvement of infrastructure during these formative years of the State, though the accusation that sentimentality was the primary grievance of the people involved is arguably unfair and misrepresentative. As one contemporary journalist wrote: “In such a community the loss of friends and neighbours is much more than a sentimental loss”. ( The Irish Independent , 6th October, 1937). Subsequently Tim Lennon, who lived with his father Matthew Lennon at Ballinahown, said of the arbitration proceedings; “we can say that the arbitration was held in Hell and that the Divil was the arbitrator”. Lennon summed up local feelings: “The feeling of the local people was that it was back to the days of Cromwell…that they were evicted whether they were willing or not and anyone who didn’t take the money, there was no sheriff needed, the dam was built and the water was the sheriff”. (From an interview with Séamas Ó Catháin on the RTE Radio Programme “Folkland”, broadcast in February 1984). In the long run, however, the landowners lost their battle for a substantial increase in compensation. The implied national importance of the scheme inevitably won the day. Construction work on the 100 feet high dam at Poulaphuca began in November 1937: “The erstwhile lonely, silent conditions in Poulaphuca waterfall district have suddenly been displaced with extraordinary hum and activity. Fifty men have already started work on the Poulaphuca scheme”. ( Leinster Leader , 13th November, 1937). Once a beauty spot famed for its waterfall and favoured by tourists for over a century, the gorge now became a massive construction site. The dam was built from both sides of the gorge, towards the centre where a culvert channelled the River Liffey through the construction site. Construction work continued round the clock on three 8-hour shifts. Much of the labour was taken on by local men. Some 10,000 cubic metres of rock were excavated for the foundations of the dam, and some 18,000 cubic metres of concrete were used in its construction. Below the dam, construction work soon began on the Power Station itself. Work also began on a pressure tunnel, 5m in diameter, cut through the bedrock in order to feed the water from behind the dam directly to the power station. Work on this tunnel was slow through the hard slate and sandstone, as little as 8 or 9m a week. Further downstream at the rapids known as the Golden Falls, construction began on a second, smaller power station. Between these two power stations a smaller reservoir was constructed to regulate the flow of water into the lower stretches of the River Liffey. With the construction of the dam under way, workmen were engaged to erect some thirty-five miles of fencing around the proposed perimeter of the lake. The fringes of the reservoir were later planted with trees as a barrier to livestock, in order to prevent contamination of the water supply. Apart from the dam and power stations, it was also necessary to construct replacement roads and three new bridges, Blessington Bridge, Burgage Bridge and Humphreystown Bridge (for an engineering description of the construction of the bridges, particularly Burgage Bridge, see W.G. Ebrill & F.G. Clinch, ‘Liffey Power Development. Design and Construction of reinforced concrete bridge’, Transactions of the Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland 67 (1940-41), 211-47). The contracts for the construction of the dam, tunnel and power station were awarded to Francois Cementation Co. Ltd, an English-based company from Doncaster, whereas the contract for the bridges was awarded to C.S. Downey. Near the dam an entire village was specially constructed for the workforce. The buildings housed some 200 men and included a canteen and billiards room. On the opposite side of the dam there were bungalows for the contractors’ representatives and the Resident Engineer, Vernon Dunbavin Harty, as well as head quarters for the engineers and inspectors. The Chief Civil Engineer for the E.S.B. was Joe Mac Donald. Both MacDonald and Harty had previously worked on the Shannon scheme. Harty described the concreting construction of the dams and power stations at Poulaphuca and the Golden Falls in a paper to the Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland in December 1940 (‘Liffey Power Development I. Concreting Methods’, Transaction of the Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland 67 (1940-41), 23-43). While the ESB pressed ahead with the construction of the dam and power stations, Dublin Corporation began work on a tunnel to take water from the reservoir to filtration and purification plants under construction at nearby Bishopsland Hill, outside Ballymore Eustace, Co. Kildare. Work also began on the construction of a 12 mile long concrete conduit to south Co. Dublin. This work was completed in 1944. For a description and history of the water works aspect of the scheme see E. Healy, C. Moriarty and G. O’Flaherty, The Book of the Liffey from source to the sea (1988). As part of the compulsory order, the E.S.B. claimed ownership of all fittings in the houses. This was to lead to an embarrassing situation with Wicklow Co. Co. when the E.S.B. reported that fittings, including fireplaces, doors and presses were found to have been removed from three labourers cottages purchased from the council. The E.S.B claimed that if the fittings were not returned that they would be obliged to review the purchasing figure (Co. Wicklow Board of Health Minutes (1939), 622). The agreement signed between the E.S.B. and Dublin Corporation in June 1936 covers a multitude of technical issues, however, most relevant here is Section 4(a), in which the E.S.B. agreed to demolish all dwellings and farm buildings, as well as to remove the burials at Burgage graveyard. The sites of these houses were then to be sanitised with a ‘sprinkling’ of chlorate of lime. Furthermore, all trees were to be removed, and all obstructions, including field fences, that might be exposed should the water levels be lowered to 575ft OD. The E.S.B. agreed to meet the costs of these preparatory works, which included the blowing up of Baltiboys Bridge by the Irish Army on 6th September, 1939. By mid-September many of the houses had been stripped and/or demolished. This was significant because it meant that any attempt to document the area had to be made before these initial clearance works began. At 10.00am on March 3rd, 1940, the sluice gate diverting the River Liffey around the completed dam was closed. The opportunity for the use of poetic licence was not lost by some reporters: “She [the Liffey] backed up, and spreading out, started to muster the forces of her ancient ally, the King’s River, three miles above, for a grand assault on her prison; but, having found it was so impregnable that the base of it was capable of withstanding a pressure of three tons to the square foot, she surrendered. Great stuff, this Irish cement!” ( The Irish Press , 24th April, 1940). Gradually the water began to build up, and by September of that year the water level had risen to one-third of the proposed area of the reservoir. During the summer of that year, in a race against the tide as it were, many local people extracted as much turf from the bogs surrounding Ballinahown as they possibly could before this important fuel source became permanently submerged. According to one newspaper account: “small boys and women with donkeys and carts, men with horse-carts work from dawn until dark to secure the fuel”. ( The Irish Press , 12th September, 1940). In August 1940, Jimmy Cullen paid a final visit to the family home in Lacken: “On that occasion he met some household articles, including a crucifix, coming out through the kitchen door on the rising tide”. (M. J. Kelly, ‘Tales from a drowned land’, Journal of West Wicklow Historical Society 1 (1983-4), 14). It is hardly a coincidence that during these early years of the Second World War the exodus from the valley became known as ‘the evacuation’. While the water levels of the reservoir were gradually rising, the mechanical plant was being delivered to the power stations. However, the Second World War had begun in earnest by this time and much of the plant required for the power stations had been specially commissioned outside the State. The war brought an almost complete cessation of shipping, and heavy engineering plants in Britain and elsewhere were prioritising the needs of war. Many of the crucial elements required for the power stations did not arrive until after the end of the war, and the main power station at Poulaphuca was not put into full commission until early 1947. Despite these setbacks, the ESB successfully began operations of its smaller power station at the Golden Falls in December 1943, and improvisations allowed limited operation of the main power plant at Poulaphuca a year later. (L. Kenny, 50 Years on the Liffey (1994), 43-4). However, it is somewhat telling that the local people, including those who had sacrificed their lands and homes for the reservoir, did not see any immediate benefits of the scheme. Finally, on 11th December 1952, as part of the diamond jubilee celebrations of Fr O’Loughlin, the priest who had opposed aspects of the reservoir scheme switched on the electricity power for the parish. Electricity was brought to these people, no longer part of an integrated community, but divided and scattered along the shores of a massive lake. For many years after, those people who were forced off their lands due to the scheme became known locally as the ‘washed outs’.

“Like the fisherman, all who know it now may then, but in dreams, look through the “waves of time” and see this valley of other days”. From an article by T.J. Molloy on the drowning of the Upper Liffey Valley for the Liffey Reservoir Scheme, The Irish Independent, 27th May, 1936. One of the largest infra-structural schemes carried-out during the formative years of the State was the Liffey Reservoir Scheme. With the construction of a dam at Poulaphuca, a large reservoir was created within the upper stretches of the River Liffey in Co. Wicklow. The reservoir was designed to supply water to Dublin city and provide additional electricity supply to the national grid. For many visitors to the area today this man-made lake seems as if it has been ever-present in the landscape. However, as the water levels of the reservoir gradually rose in 1940 it submerged a historic landscape that only a few months previously hosted a thriving farming community. Poulaphuca area The River Liffey, synonymous with Dublin City, has its origins high in the Wicklow Mountains. At the point where the river arrives at the foothills of the Wicklow Mountains it entered a basin-like landscape, subsequently flooded by the reservoir. Towards the end of the last Ice Age the basin-like area was formed by a massive lake of melt water. Rather than taking a direct route to the sea, the Liffey was forced south through this natural basin, finally exiting to the plains of Kildare at the natural chasm at Poulaphuca, which was for many years favoured by tourists who came to see the dramatic falls. The construction of the hydro-electric dam reduced the tumbling waters at Poulaphuca to a mere trickle. A large section of the King’s River, which joined the Liffey at Burgage was also flooded. The high ridge at Baltiboys separated the Liffey Valley from the King’s River Valley, and today forms a peninsula extending into the southern part of the reservoir. Prior to the flooding by the reservoir the area did not form a clearly defined geographical unit. The landscape to the west consisted of rolling gravel ridges, providing reasonably fertile land. Here the land dropped steeply to the plains alongside the Liffey. These plains were marshy meadows prone to flooding by the Liffey itself, but the land was generally quite fertile. Above these low-lying plains the fertile land attracted large estates in the 18th century, including Russborough, Russellstown, Tulfarris, Baltiboys and Blessington Demesne. Along the east the area was dominated by the Wicklow Mountains. The low-lying land between the Liffey, the King’s River and the mountains was boggy, drained by a number of small streams, but mostly capturing the run-off water from the mountains. This land developed as small farm holdings, and those on the fringes of the basin also held land on the rising mountain slopes. The townlands most affected by the reservoir were Baltiboys, Ballyknockan, Burgage, Humphreystown, Lacken, Monamuck and Russellstown. In the middle of these was Ballinahown, which was completely removed from the map by the flooding. Contrary to more recent mythology, no villages (or churches) were flooded by the reservoir, these were all spread around the area that was to be flooded; Manor Kilbride to the north, Lacken and Ballyknockan along the east, Valleymount at the south, and the town of Blessington at the west. Where the people of Lacken and Ballyknockan now look onto a shimmering lake, the people before them once looked over farms and bog. Origins of the Liffey Reservoir Scheme The proximity of the upper reaches of the River Liffey to Dublin attracted many to the potentials of the river as a source of water-driven power. Even before the foundation of the State a British Government commission, established in 1919 to examine Ireland’s waterpower resources, argued in favour of the River Liffey as a primary candidate for generating stations. The water flow of the Liffey was insufficient in itself to power electricity generating stations, however, this could be overcome with the creation of a reservoir to provide a manageable water supply. The natural basin-like landscape of the upper reaches of the River Liffey and King’s River was an obvious choice for such a massive reservoir. In 1923 and 1924 there were a number of proposals to the Dáil for electrification schemes aimed at harnessing the River Liffey. These included Dublin Corporation’s ‘Dublin and District Electricity Supply Bill’, Sir John Purser Griffith’s ‘Dublin Electricity Supply Bill’ and ‘Dublin Electricity Supply Bill’ introduced by Anna Liffey Power Development Co. Ltd. One of these, the East Leinster Electricity Supply Bill, submitted by J.F. Crowley and Partners, was remarkably similar to the scheme finally adopted by the E.S.B. a decade later. Despite this, a powerful lobby argued more strongly in favour of exploiting the River Shannon, and these more adventurous proposals were approved in June 1925. However, the electrification of Ireland was still in its infancy and it was recognised by some that the economic development of the State would require an expansion of the electrification scheme. Not long after the Shannon Scheme came into operation it became clear that consumer needs were rapidly increasing beyond the capacity that could be provided. In 1925 there were some 36,000 consumers of electricity. By 1936 this number had dramatically increased to 130,000. Not unrelated to the rise in consumption of electricity was the contemporary expansion of Dublin’s suburbs, which required infrastructural investment, in particular an expansion of water supply. With the coming to power of a Fianna Fail government in 1932, a government driven by policies of self-sufficiency, the Liffey Scheme was again actively pursued. In 1922 a water level gauge had been installed at Poulaphuca gorge and over the following years daily readings were taken of the flow of the River Liffey. Geological borings and trial holes from Blessington to Poulaphuca had resolved initial concerns about the water retention capabilities of the gravel ridges along the western perimeter of the required reservoir. All the available data showed that the proposed reservoir for the hydro-electric scheme would be viable. However, it was not the E.S.B. who actively pursued the proposals for a reservoir at Poulaphuca, instead this role was adopted by Dublin Corporation, Dublin County Council and the other local authorities in that county. The water shortage was discussed at a special meeting of Dublin County Council in February 1936. The Chairman Patrick Belton (TD) “said that the Poulaphuca scheme was considered to be the only solution.” (Leinster Leader, 15th February, 1936). The costs of the scheme could not be borne by the Corporation and the County Council alone, and required the involvement of the E.S.B. through the Department of Industry and Commerce. It appears that the Corporation and County Council felt that the water shortage had reached a critical point, and that the urgency was not being taken seriously by the Department. At a meeting later that month: “Dublin Co. Co. decided on the motion of the Chairman (Mr Patrick Belton, T.D.) to request from the Minister for Industry and Commerce an immediate decision as to whether the Poulaphuca joint hydro-electric scheme would be undertaken without delay. The Council otherwise would petition the President to have the obstacles placed in the way of an adequate supply of water for the city and county by the Minister for Industry and Commerce and the E.S.B. removed immediately, so that a water famine might be averted.” (Leinster Leader, 29th February, 1936). On 8th June, 1936, an agreement was signed between the E.S.B. and Dublin Corporation, setting out the details for the scheme. The Poulaphuca scheme, or Liffey Reservoir Scheme as it was officially known, came on stream with the introduction in November 1936 of the Liffey Reservoir Bill to the Dáil by a future Taoiseach, Seán Lemass, then Minister for Industry and Commerce. In his introduction to the bill, Lemass said: “It will be gathered from what I have already said that such a supplementary scheme was not one of immediate urgency from the view-point of the Electricity Supply Board, but nevertheless, it was felt that it would prove of definite economic value eventually and that the best results could be achieved by the Corporation and the Electricity Supply Board uniting in carrying out a scheme which would meet both their purposes”. ( Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 54. 4th November, 1936). There immediately followed an intense debate in the Dáil, centred around the proposed compulsory purchase powers to be given to the E.S.B., and in particular the method of compensation to farmers that would only allow for the value of the land as it stood at that time of depression, and not on the higher values of ten years earlier. The O’Mahony reacted by saying of the Minister: “He has drawn attention to all the great benefits which are going to be received by the vast majority of the people concerned. Enormous benefits are going to be conferred on the people of Dublin, not only the people who live there at the present moment, but on the people of Dublin in future generations. But not one word has yet been said with regard to the unfortunate people who are going to lose their homes…..They are a small minority who are going to confer great and vast benefits on Dublin and on the surrounding areas, and also with regard to the supply of electricity vast benefits are going to be conferred on the whole Saorstát. Not only are they conferring those benefits on people living today, but on generations yet born”. (Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 58). The O’Mahony continued: “There are certain people in that district who may have only a small bit of land. Some people might regard it as merely a little bit of bog, but it is their home and not only their home but their main source of living. It is not alone that they enjoy that little plot of land but they have the right of grazing on the mountains. Unless they can get a similar home within reasonable distance of the mountains they will lose their main source of livelihood ….. I was over there last Sunday at a meeting and it was really piteous to see the state of uncertainty in which these people were. They did not know where they were. After all is said and done, the Minister and rest of us when we go to bed tonight will not have to worry as to whether or not we are going to lose our homes. Every night these men when they go to bed wonder what is going to happen to them and what is going to be done for them, and whether they are going to get the treatment they expect – fair treatment – from an Irish Government”. (Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 61-2). It is clear that the members of the Dáil were aware of the many issues that affected those people who would be forced to move to make way for the reservoir, though it is arguable to what level they understood or were sympathetic of these issues. Indeed, they seem to have been deliberately played down by some Deputies. For example, Thomas Kelly claimed: “I do not think that the doleful tales which the Deputies from Wicklow have put before the House today are necessary…..They will get ample compensation, sufficient to recompense them for even any sentimental values attached to their old homes.” (Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 71-2). During the Committee Stage the issue of compensation was again discussed. In particular, The O’Mahony proposed an amendment that would base the compensation estimates on the average value of the land during the years 1928-1930, plus 50% of such an estimated value by way of compensation for disturbance. The O’Mahony argued that the compensation based on the value of the land in 1936 when the Bill was introduced was inherently unfair given the poor value of the land at that time, as a result of the Economic War with Britain. William T. Cosgrave, whose government had sponsored the Shannon Scheme, argued: “Our case is not against the justice of the compensation basis. Our case is that this land is being taken at a time when, owing to circumstances for which those farmers are not responsible, its value is at a low ebb”. (Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 601). The amendment was defeated. While the ESB would later take the blame for the rates of compensation offered to those affected by the scheme, it is clear from the Dáil Debates that the issue of rates of compensation to be offered to landowners was a Government-led decision. Others questioned the viability of the scheme. When pressed on this during the Committee Stage, Lemass finally admitted that: “I was explaining to the Dail that the ESB if it were merely concerned with its own business would not proceed with this development at the moment. It is proceeding with this development because it has made an agreement with the Dublin Corporation to do so – an agreement which arose out of the special needs of the Corporation”. (Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 559. 18th November, 1936). This further highlights the primary motive behind the emphasis on the Poulaphuca Scheme, in which the provision of electricity was secondary to the increasing needs of Dublin City and County for a water supply. This is reflected in the estimated costs of the project. The costs of the construction of the dam and all ancillary works, including new bridges and roads, as well as the clearance of the area to be flooded, was estimated to be in the region of £760,000. Dublin Corporation agreed to contribute a sum of £126,000 to the costs of this aspect of the project. However, the Corporation had their own costs to bear, and the construction of the filter beds and the main to feed water into the city were estimated to cost £694,000 (Dáil Debates, Vol. 64, 55. It was estimated that the dam and civil construction works would cost £387, 000, the roads, bridges and acquisitions of lands £183, 000, and the mechanical-electrical works and equipment £190, 000). As part of the agreement signed between the E.S.B. and Dublin Corporation in June 1936, the Corporation was entitled to use not more than 20 million gallons (90 million litres) of water a day. The initial proposal for a reservoir at Poulaphuca was greeted by many as a wonderful opportunity to provide a variety of amenities. According to one newspaper correspondent: “A few years hence…instead of getting out its cars to go picnicking on the golden strands of the coast on a summer afternoon, Dublin will probably be speeding to the sophisticated park-like shores of the great inland sea in the midst of the Wicklow Mountains. Where now lie thousands of acres of bog and poor pastureland will then lie an immense shimmering sheet of oriental water. Boats with coloured sails and dipping oars will be skimming over its calm surface”. (The Irish Independent, 27th May, 1936). For many people who lived in the area the concept of a large lake offering leisure and sporting amenities was an alien one.