by Christiaan Corlett

•

15 September 2019

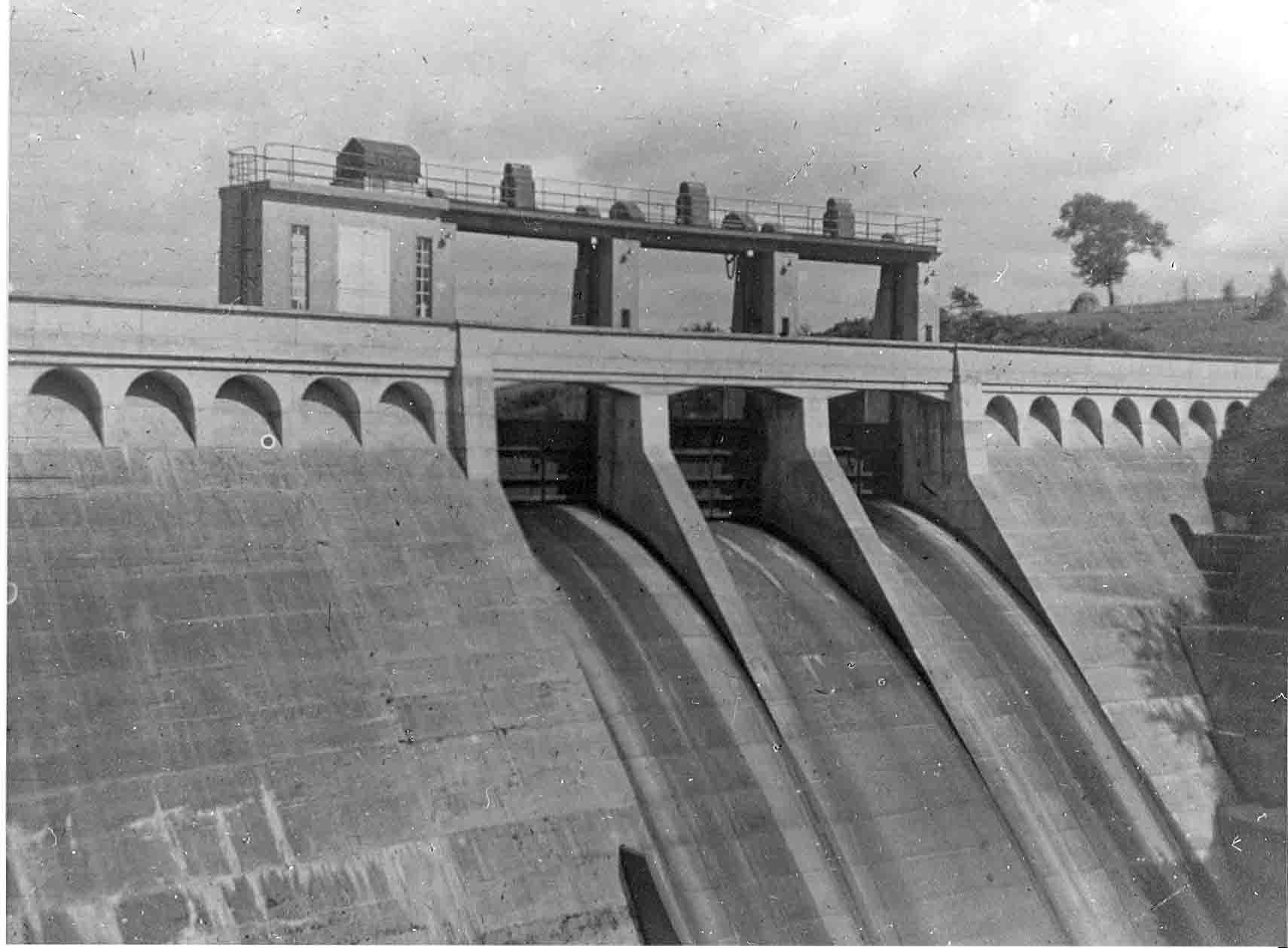

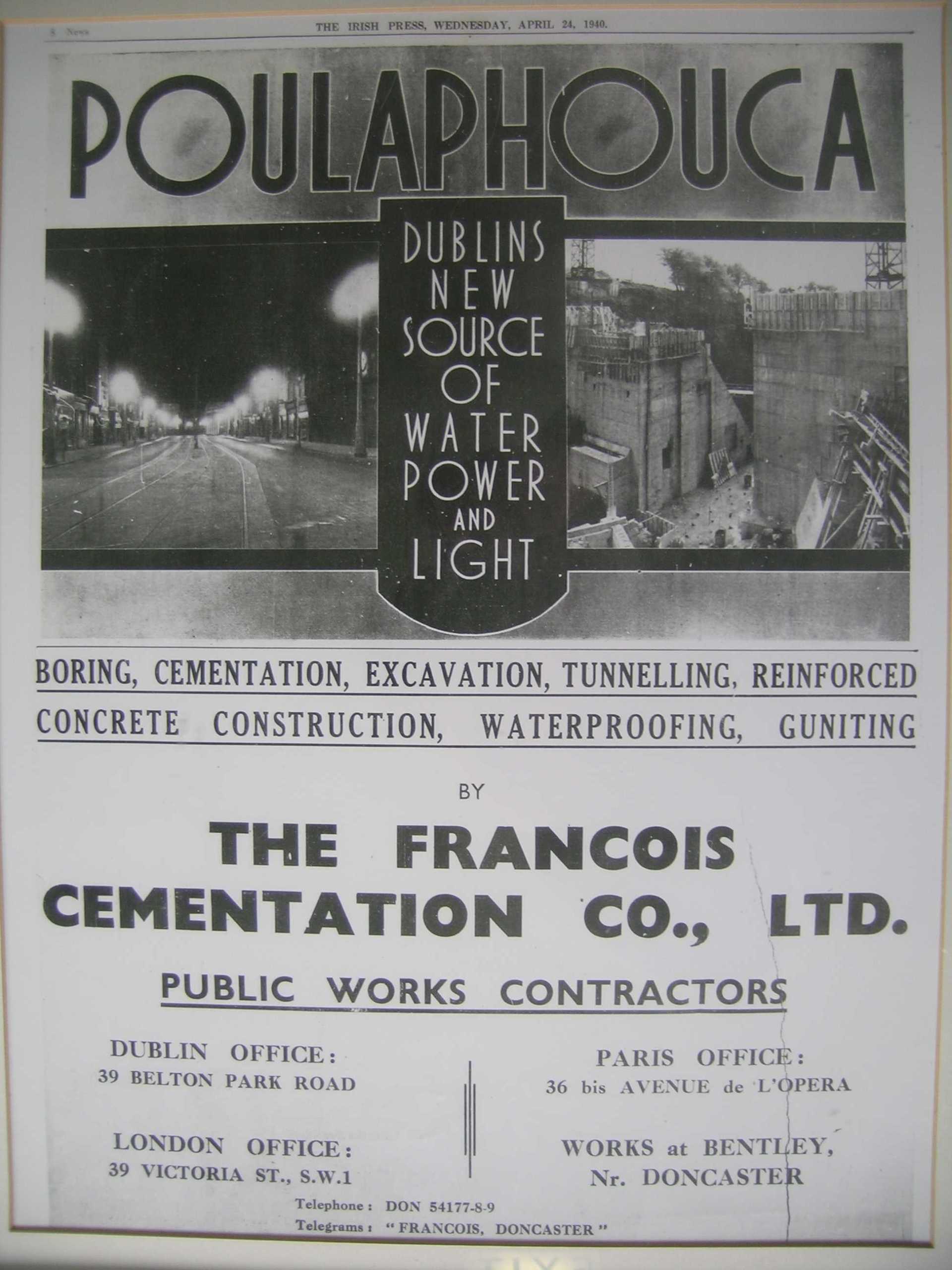

The target for the reservoir was the flooding of all the land in the area below the 188.4m (612ft) OD, with an aim of maintaining the low water level at no lower than 177 m (580ft) OD. Taking the 612ft OD as an average level of the reservoir, some 4960 acres (2007 hectares) would be flooded, creating a shoreline of over 30 miles. Additional to this, the E.S.B. also required a sufficient buffer area between the reservoir and the surrounding agricultural area, in case there was a need to raise the lake levels, and also to prevent contamination of the drinking water by farming. This buffer area was subsequently planted with forestry in order to prevent stock from gaining access to the reservoir, and to limit human access to the reservoir also. In effect over 5,500 acres (2225 hectares) would be affected by the proposed reservoir, including some 55 residential holdings and 12 labourers cottages, 50 farms and extensive bog land used for fuel by local families from a wide area. Some of the houses would not be flooded by the reservoir, however, in order to ensure the necessary quality of the water as a water supply, houses situated beside the proposed shoreline were to be purchased and demolished. The issues concerning compensation did not go away after the passing of the Liffey Reservoir Bill at the end of 1936. Indeed, it would become the focus of much resentment. Local political representations argued that the proposed measures could not compensate for the loss of independence that would impact certain farmers, and that there would be no compensation for disturbance caused to those forced to move. In particular, farmers whose holdings would be partially covered by the reservoir would also only receive compensation for the acquired land at market value, without any consideration of the impact the reduction of their farmland would have on their livelihoods. Speaking to one farmer who would be affected in this way, a journalist reported: “I talked to a man with thirty acres of land, twenty of which – and the best twenty – he expects to lose. He asked, reasonably; “What use is this house and ten acres of poorish mountain land? I cannot live on it, but I will not be compensated for the house, because it will not be flooded”. ( The Irish Independent , 6th October, 1937). For these farmers, who used much of the low lying ground as grazing for dairy farming, the loss of this land meant that they would be forced upland. This land was not suitable for dairy stock all year round, and meant that these farmers would be forced to change to another form of farming, such as sheep. There were also concerns about the effects of the reservoir on the holy well known as St. Bodin’s Well at Templebodin. According to tradition there were two fish in the well, which would escape once the area was flooded, thereby causing the well to loose its power (National Folklore Collection, Schools Manuscripts 913:131). There is a hint of sarcasm in a correspondent writing in the Irish Press: “Perhaps the believers in the old tradition will shake their heads in doubting; perhaps they will make the best of it and relate how it is that the Liffey hydro-electric scheme assumes its power from a blessed well”. ( The Irish Press, 28th March, 1938). This reflects a general change of attitude during this period, one which turned its back on the old ways, and saw not just the electric revolution, but also the scheme itself and the use of this technology to harness the power of electricity, as a means towards achieving a modern Ireland. One newspaper reporter wrote: “The seanachaidhe frowned. Who now would listen to the titanic prowess of the legendary heroes of old, when a number of ordinary, present-day mortals, without the aid of any magic wands or magic hokus-pokus, could transmute Anna Liffey into a form of tamed lightening that could do their bidding at will in a number of fantastic operations, such as lighting a whole city thirty miles away, driving trains, unloading ships, curling ladies locks, shaving men’s faces, taking pictures of people’s insides and throwing the voices of child prodigies, prophets and the like from one end of the world to another through the ethereal void in less than one flick of a Wicklow lamb’s tail – all sorts of things like that out of just ordinary water!” ( The Irish Press , 24th April, 1940). The protracted nature of the proposed scheme appears to have weakened any desire to vigorously oppose the scheme when it was finally proposed officially. This is evident from a newspaper report in 1936: “Ballinahown, while doomed, is prepared to accept what the future holds. “Eleven years ago”, I was told, “something like this was in the air, but they went off to the Shannon, and built there. Two years ago there was more talk about water works”. On that occasion, it would appear, notice was given to people who would be affected that their homes should not be repaired or added to in any costly nature. Since then no other information has been received, but, as the man here in the heart of affairs told me, “they mean business this time”.” ( The Irish Independent , 27th May, 1936. The informant was not named, but may have been one of the Quinn’s of Ballinahown). In an interview with John Quinn of Ballinahown in 1937, a journalist provides a valuable insight into the psychological effect the imminence of the scheme had on the communities: “He states that for the last ten years this depressing threat of dispossession has retarded development. He had noticed it depressing the young, progressive farmers, chilling their enthusiasm” ( The Irish Independent , 6th October, 1937). Local resentment was aired at several meetings held in the area during 1938 and 1939. Fr Francis O’Loughlin, Parish Priest of Valleymount was also critical of the scheme, and together with some local politicians, set up The Disturbed Owners Association to highlight deficiencies in the plan. The Chairman of the Association was Peter P. O’Reilly, who, in an interview with the Irish Press, came out in support of his fellow Ballyknockan stone cutters: “Above the valley 500 men work at the quarries. They are trade unionists, they care not for any other trade; they depend on the valley, some of them for produce of little gardens which they have patchworked into its marshes after years of toil, their work being from father to son; those who do not actually dwell in the valley, but in the foothills, depend on it for the grazing of their few cows, for turf from its bogs, their only source of fuel.” ( The Irish Press , 20th April, 1938). At the beginning of October 1938 a large protest meeting was held at Lacken. At this meeting many of the concerns were discussed, not for the first time. At the outset the chair of the meeting, Martin Murphy of Carrig, claimed that “no one was officially informed of his position, and the only notification they got at the start of the proceedings was from a map which was sent to the local Garda Station”. It would appear that even at this stage there was much confusion as to when people would be required to leave their houses and farms. There was also much resentment against the compensation offers made by the E.S.B., which were claimed by some to have been as much as £200 and £300 less that the estimates of the land valuers. At the end of the meeting a resolution was passed unanimously: “That we, the farmers of Blessington, Lacken and Valleymount, view with alarm the inadequate compensation offered by the Electricity Supply Board for our lands which are acquired for the Liffey Hydro Electric Scheme. The prices fixed in the original offers were considerably below the ordinary land values, and having regard to the consequential losses which will be entailed by all affected, and considering that we are forced from our lands against our will, we demand the fullest measure of consideration. In the event of arbitration, we demand that the arbitration court consists of one of the Electricity Supply Board, and an independent Chairman, who will be mutually agreed upon by both parties”. ( Leinster Leader , 8th October, 1938). Arbitration proceedings were held at Blessington in October 1938 for those who were dissatisfied with the standard compensation rate offered to them. A newspaper correspondent reported that at the opening of the proceedings John A. Costello, K.C., for the E.S.B (and future Taoiseach) refuted the perception that the arbitrator, J.J. McAuley, would be in some way biased in favour of the E.S.B. He stated that the appointment had been made by an independent committee, consisting of the Chief Justice, the President of the High Court and the President of the Institute of Civil Engineers. He further stated: “The E.S.B. had been charged by an Act with the gravest public responsibility and duty in connection with this scheme. A great hardship would undoubtedly be caused to individuals, but public purposes had a right to over-ride private grievance. The Board fully appreciated that numbers of these people would be dispossessed of their lands in which they had lived for generations, and that no amount of money would adequately compensate them for their sentimental loss or the sentimental value they attached to their holdings. The principle they had to follow, however, was laid down in the Liffey Act and there was nothing new in this principle on which the compensation must be assessed.” (Quotation of correspondent reporting in The Wicklow People , 15th October, 1938). Clearly there was no tolerance of sentimentality in the momentum for the improvement of infrastructure during these formative years of the State, though the accusation that sentimentality was the primary grievance of the people involved is arguably unfair and misrepresentative. As one contemporary journalist wrote: “In such a community the loss of friends and neighbours is much more than a sentimental loss”. ( The Irish Independent , 6th October, 1937). Subsequently Tim Lennon, who lived with his father Matthew Lennon at Ballinahown, said of the arbitration proceedings; “we can say that the arbitration was held in Hell and that the Divil was the arbitrator”. Lennon summed up local feelings: “The feeling of the local people was that it was back to the days of Cromwell…that they were evicted whether they were willing or not and anyone who didn’t take the money, there was no sheriff needed, the dam was built and the water was the sheriff”. (From an interview with Séamas Ó Catháin on the RTE Radio Programme “Folkland”, broadcast in February 1984). In the long run, however, the landowners lost their battle for a substantial increase in compensation. The implied national importance of the scheme inevitably won the day. Construction work on the 100 feet high dam at Poulaphuca began in November 1937: “The erstwhile lonely, silent conditions in Poulaphuca waterfall district have suddenly been displaced with extraordinary hum and activity. Fifty men have already started work on the Poulaphuca scheme”. ( Leinster Leader , 13th November, 1937). Once a beauty spot famed for its waterfall and favoured by tourists for over a century, the gorge now became a massive construction site. The dam was built from both sides of the gorge, towards the centre where a culvert channelled the River Liffey through the construction site. Construction work continued round the clock on three 8-hour shifts. Much of the labour was taken on by local men. Some 10,000 cubic metres of rock were excavated for the foundations of the dam, and some 18,000 cubic metres of concrete were used in its construction. Below the dam, construction work soon began on the Power Station itself. Work also began on a pressure tunnel, 5m in diameter, cut through the bedrock in order to feed the water from behind the dam directly to the power station. Work on this tunnel was slow through the hard slate and sandstone, as little as 8 or 9m a week. Further downstream at the rapids known as the Golden Falls, construction began on a second, smaller power station. Between these two power stations a smaller reservoir was constructed to regulate the flow of water into the lower stretches of the River Liffey. With the construction of the dam under way, workmen were engaged to erect some thirty-five miles of fencing around the proposed perimeter of the lake. The fringes of the reservoir were later planted with trees as a barrier to livestock, in order to prevent contamination of the water supply. Apart from the dam and power stations, it was also necessary to construct replacement roads and three new bridges, Blessington Bridge, Burgage Bridge and Humphreystown Bridge (for an engineering description of the construction of the bridges, particularly Burgage Bridge, see W.G. Ebrill & F.G. Clinch, ‘Liffey Power Development. Design and Construction of reinforced concrete bridge’, Transactions of the Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland 67 (1940-41), 211-47). The contracts for the construction of the dam, tunnel and power station were awarded to Francois Cementation Co. Ltd, an English-based company from Doncaster, whereas the contract for the bridges was awarded to C.S. Downey. Near the dam an entire village was specially constructed for the workforce. The buildings housed some 200 men and included a canteen and billiards room. On the opposite side of the dam there were bungalows for the contractors’ representatives and the Resident Engineer, Vernon Dunbavin Harty, as well as head quarters for the engineers and inspectors. The Chief Civil Engineer for the E.S.B. was Joe Mac Donald. Both MacDonald and Harty had previously worked on the Shannon scheme. Harty described the concreting construction of the dams and power stations at Poulaphuca and the Golden Falls in a paper to the Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland in December 1940 (‘Liffey Power Development I. Concreting Methods’, Transaction of the Institution of Civil Engineers of Ireland 67 (1940-41), 23-43). While the ESB pressed ahead with the construction of the dam and power stations, Dublin Corporation began work on a tunnel to take water from the reservoir to filtration and purification plants under construction at nearby Bishopsland Hill, outside Ballymore Eustace, Co. Kildare. Work also began on the construction of a 12 mile long concrete conduit to south Co. Dublin. This work was completed in 1944. For a description and history of the water works aspect of the scheme see E. Healy, C. Moriarty and G. O’Flaherty, The Book of the Liffey from source to the sea (1988). As part of the compulsory order, the E.S.B. claimed ownership of all fittings in the houses. This was to lead to an embarrassing situation with Wicklow Co. Co. when the E.S.B. reported that fittings, including fireplaces, doors and presses were found to have been removed from three labourers cottages purchased from the council. The E.S.B claimed that if the fittings were not returned that they would be obliged to review the purchasing figure (Co. Wicklow Board of Health Minutes (1939), 622). The agreement signed between the E.S.B. and Dublin Corporation in June 1936 covers a multitude of technical issues, however, most relevant here is Section 4(a), in which the E.S.B. agreed to demolish all dwellings and farm buildings, as well as to remove the burials at Burgage graveyard. The sites of these houses were then to be sanitised with a ‘sprinkling’ of chlorate of lime. Furthermore, all trees were to be removed, and all obstructions, including field fences, that might be exposed should the water levels be lowered to 575ft OD. The E.S.B. agreed to meet the costs of these preparatory works, which included the blowing up of Baltiboys Bridge by the Irish Army on 6th September, 1939. By mid-September many of the houses had been stripped and/or demolished. This was significant because it meant that any attempt to document the area had to be made before these initial clearance works began. At 10.00am on March 3rd, 1940, the sluice gate diverting the River Liffey around the completed dam was closed. The opportunity for the use of poetic licence was not lost by some reporters: “She [the Liffey] backed up, and spreading out, started to muster the forces of her ancient ally, the King’s River, three miles above, for a grand assault on her prison; but, having found it was so impregnable that the base of it was capable of withstanding a pressure of three tons to the square foot, she surrendered. Great stuff, this Irish cement!” ( The Irish Press , 24th April, 1940). Gradually the water began to build up, and by September of that year the water level had risen to one-third of the proposed area of the reservoir. During the summer of that year, in a race against the tide as it were, many local people extracted as much turf from the bogs surrounding Ballinahown as they possibly could before this important fuel source became permanently submerged. According to one newspaper account: “small boys and women with donkeys and carts, men with horse-carts work from dawn until dark to secure the fuel”. ( The Irish Press , 12th September, 1940). In August 1940, Jimmy Cullen paid a final visit to the family home in Lacken: “On that occasion he met some household articles, including a crucifix, coming out through the kitchen door on the rising tide”. (M. J. Kelly, ‘Tales from a drowned land’, Journal of West Wicklow Historical Society 1 (1983-4), 14). It is hardly a coincidence that during these early years of the Second World War the exodus from the valley became known as ‘the evacuation’. While the water levels of the reservoir were gradually rising, the mechanical plant was being delivered to the power stations. However, the Second World War had begun in earnest by this time and much of the plant required for the power stations had been specially commissioned outside the State. The war brought an almost complete cessation of shipping, and heavy engineering plants in Britain and elsewhere were prioritising the needs of war. Many of the crucial elements required for the power stations did not arrive until after the end of the war, and the main power station at Poulaphuca was not put into full commission until early 1947. Despite these setbacks, the ESB successfully began operations of its smaller power station at the Golden Falls in December 1943, and improvisations allowed limited operation of the main power plant at Poulaphuca a year later. (L. Kenny, 50 Years on the Liffey (1994), 43-4). However, it is somewhat telling that the local people, including those who had sacrificed their lands and homes for the reservoir, did not see any immediate benefits of the scheme. Finally, on 11th December 1952, as part of the diamond jubilee celebrations of Fr O’Loughlin, the priest who had opposed aspects of the reservoir scheme switched on the electricity power for the parish. Electricity was brought to these people, no longer part of an integrated community, but divided and scattered along the shores of a massive lake. For many years after, those people who were forced off their lands due to the scheme became known locally as the ‘washed outs’.